The River Murray Weirs – Part 1 of 3: Why so many Weirs?

The River Murray Weirs were constructed 100 years ago for riverboat navigation and to supply water to inland communities. But the weirs have also degraded wetlands, salinised floodplains and devastated fish populations.

In this article I describe the origin and purpose of the River Murray weirs. In the next articles I will describe their impacts and how they are now being operated to achieve environmental outcomes.

Introduction

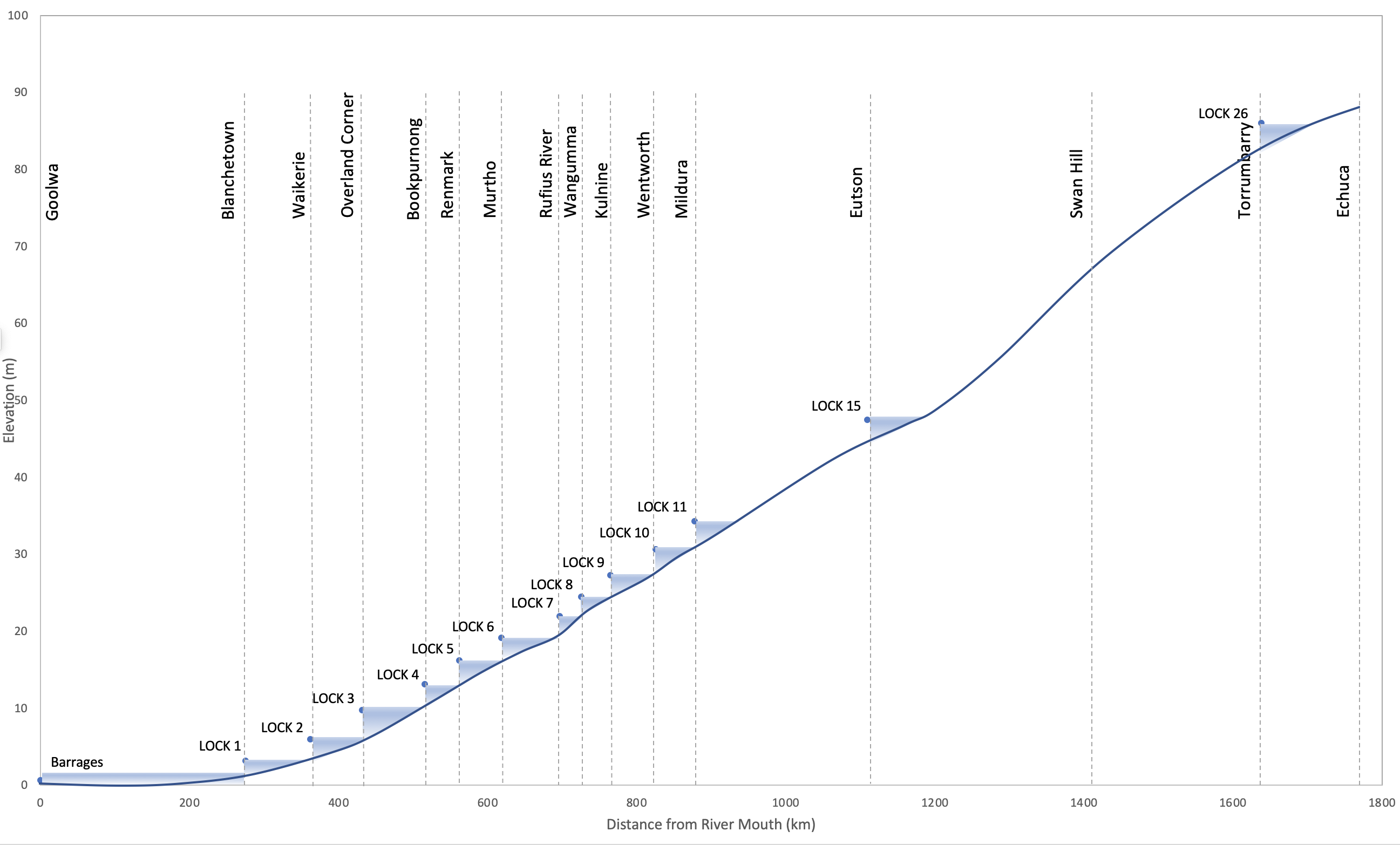

There are thirteen weirs on the River Murray between the Goolwa and Echuca.

Weirs 1 to 11 were built in a continuous series from Blanchetown to Mildura. No more were built until Weir 15 at Euston with another gap to Weir 26 at Torrumbarry.

The weirs were anticipated for fifty years before they were built, but when they were finally completed they were already out of date. Their peculiar numbering and spacing reflects the decline of the river boats, interstate rivalry and the rise of irrigation, road and rail.

Opening the Basin

In the 1850s the Murray Basin was being developed for wheat, wool, sheep and cattle.

The distances from the inland farms to the coastal ports were enormous. Sheep and cattle could be walked to markets, but wheat and wool had to be carted by bullock dray on bad roads over hundreds of miles.

As the only colony with a sea port on the Murray, South Australia wanted to develop the river as a highway to the inland. To start the river trade, in 1854 the government offered a prize for the first boat to reach the Darling River from the river port of Goolwa. Two boats competed and both passed the Darling. And they both returned with cargoes of wool – one from Swan Hill and the other from Echuca 1,570 km upstream.

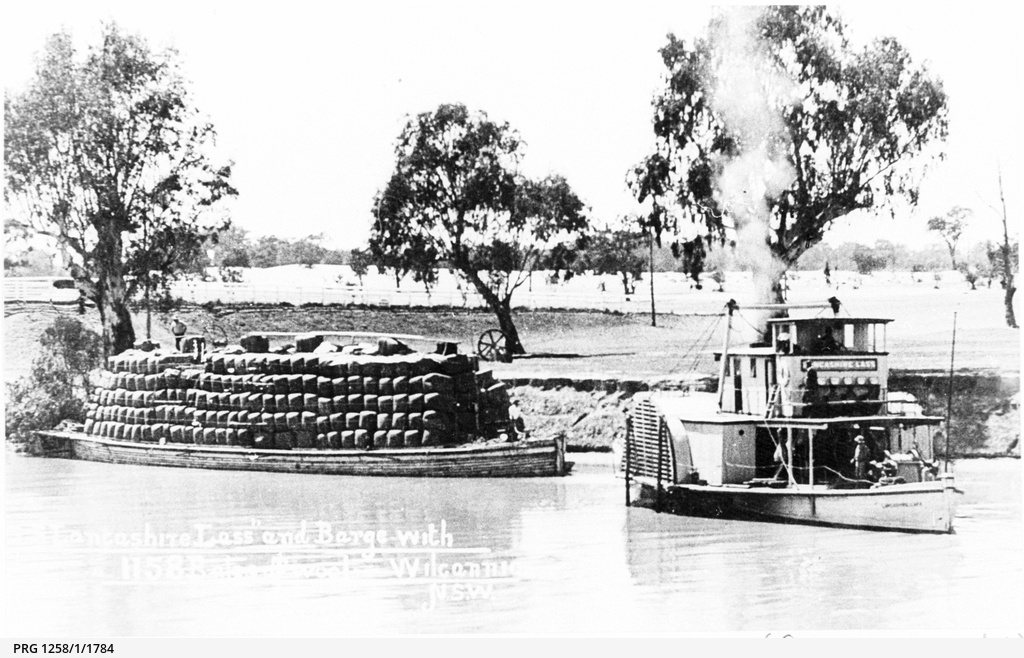

The Murray Basin was open for business. The river trade boomed and by the 1870s there were hundreds of boats working on the river. Boats travelled inland with food, people and equipment and returned with wool, wheat and timber.

PS Lancashire Lass at Wilcannia towing a barge loaded with wool. State Library of South Australia.

Navigation and Irrigation

River boats were always at the mercy of flow. Traffic would shut down in summer when discharge fell, and drought could strand river boats for years. South Australia wanted to build weirs that would keep river levels high throughout the year, and in 1863 approached the upstream colonies to discuss the proposal.

South Australia had some influence with Victoria and New South Wales while it dominated the river trade. But its position was weakened in 1864 when Victoria completed a rail line to the river port of Echuca and created an upstream alternative to Goolwa.

In fact the upstream colonies were becoming less interested in river transport than in water security. Farmers in Victoria and New South Wales were frustrated by low river flows and lobbied for a reliable supply to protect them from drought and to pursue irrigation.

South Australia looked on anxiously. Irrigation extractions would prolong low-flow periods and make navigation even harder. But worse was the scale of the plans being considered upstream. In 1886 New South Wales and Victoria signed an agreement asserting that all the water upstream of South Australia belonged to them. All of the flow to South Australia was under threat.

Discussions between the colonies were bitter, self-interested and unproductive.

PS Wanera entering Lock 4. State Library of South Australia.

Federation and the Corowa Conference

The 1902 Federation Drought forced the newly federated states to negotiate. Rainfall and river flow were at record lows. The survival of Murray-Darling farms and towns was threatened. Frustrated farmers called a conference at Corowa to discuss water security and dragged state and Commonwealth politicians to the table.

The conference agreed to important principles, including a minimum flow for South Australia and weirs for navigation and water supply. However none of the states were entirely satisfied with the outcome.

In particular, South Australia was unhappy with the low priority given to navigation.

Victoria cannot have been impressed with South Australia’s demands. They had completed a second rail line to Swan Hill in 1890, and the Mildura line was due for completion in 1903. New South Wales had also built lines to Albury, Hay and Bourke between 1881 and 1885, anticipating the demise of the river boats. Neither state was interested in a huge weir infrastructure project of questionable benefit that would sell their produce down the river.

Regardless, South Australia worked urgently to keep the river trade afloat. They passed their own legislation in 1905 to investigate weir sites and in 1910 they passed the Murray Works Act authorising nine navigation and water supply weirs from Blanchetown to Wentworth.

These plans came under a national framework when finally, in 1914, the River Murray Waters Agreement (which became the River Murray Waters Act in 1915) was signed by the states and Commonwealth. This provided for the construction of:

- a storage on the upper Murray

- a storage at Lake Victoria

- twenty six weirs and locks on the River Murray from Blanchetown to Echuca

- nine weirs and locks in New South Wales, either on the Murrumbidgee or the Darling.

South Australia began work on the first weir at Blanchetown the following year.

The New River

South Australia completed the first nine of the agreed twenty six weirs.

But New South Wales built only four of the remaining structures – Lock 10 at Wentworth, Lock 11 at Mildura, Lock 15 at Euston and Lock 26 at Torrumbarry. Of the nine proposed Murrumbidgee weirs, only two were built and they did not even include locks for riverboats to pass.

Even as the weirs were being completed it was clear that the age of the river boats had ended. In 1934 The River Murray Waters Act was amended to acknowledge that the last thirteen weirs would never be built.

River Murray weirs – elevation and distance from the Murray Mouth.

Legacy

The struggling river trade was finally killed off after the First World War by the rise of road transport.

But the river trade left a permanent mark on the river. The lower 878 km of the river became impounded in a continuous series of stepped pools.

The weirs primarily became a resource for water supply. The weirs at Torrumbarry, Euston, Mildura and Wentworth each enabled major irrigation developments. South Australia’s weirs were also used to develop extensive irrigation in the Riverland.

The weirs provided a stable and reliable source of water from which to pump. However this has become less important over time, as pumps have improved and upstream storages have become more effective in regulating flow. Several weirs support little or no irrigation.

Next Post

My next post will be about the environmental impacts of weirs. My third and final post on the River Murray weirs will describe how they are now being managed to reduce their impacts and promote ecological outcomes.

Sources and Further Reading

Connell, D. (2007). Water Politics in the Murray-Darling Basin. The Federation Press, Annandale.

Institution of Engineers, Australia (2001). The Engineering Works of the River Murray. Nomination for a National Engineering Landmark on the Centenary of Federation 2001. Institution of Engineers, Australia.

Stagg, H. (2015). Harnessing the River Murray. Helen Stagg, Mildura.

Webster, A. (2017). A colonial history of the River Murray Dispute. Adelaide Law Review, 38: 13-47.